Content Analyst

My theory is that a business’s home page should first of all make it clear who the company is and what they’re selling.

If you’re a company that’s new or different, you won’t fit into the templates. The templates will obscure what is unique about you.

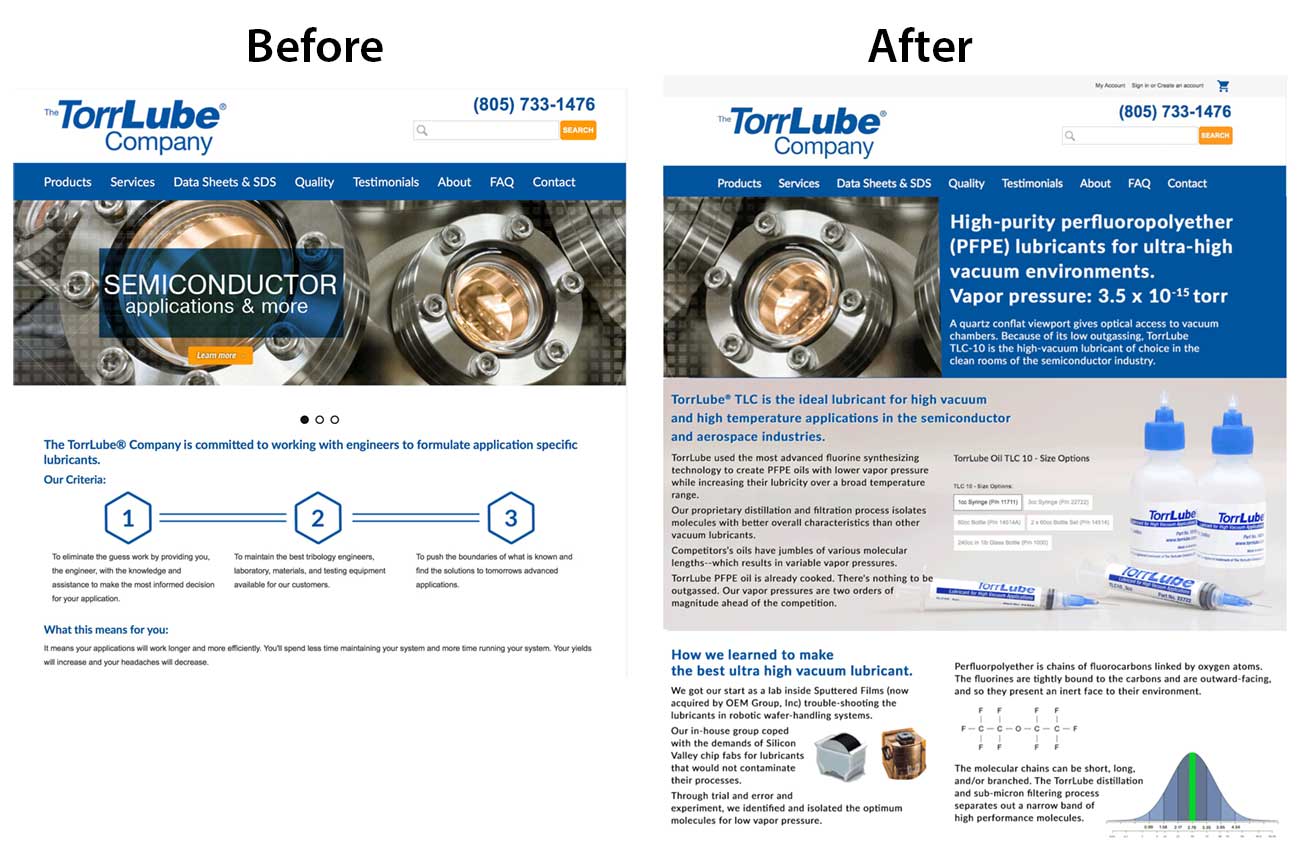

Here’s what I did for TorrLube, a small company that for twenty years has been selling a specialty lubricant called PFPE to the semiconductor industry for $5,000 a pint.

TorrLube was disappointed in their website’s lack of success–virtually zero sales.

My analysis showed that the home page at BigCommerce.com did not offer anything for sale and gave you only aspirational generalities about tribology.

Torr-Lube’s site used a low-cost template that was designed to sell different flavors of chewing gum. There was no place in the template for explaining why this particular flavor of perfluoropolyether was worth such a high price.

The site made no effort to tell you anything except the part numbers and prices of the various sizes and containers for their single product.

Their home page told you nothing concrete about the company, just abstractions and opinion.

Original site:

Okay, you do learn that they do something regarding semiconductors. I asked the CEO and the marketing director what those things are in the photo, and they didn’t know.

The site was not designed to help the reader make a choice. It was designed as a price sheet for existing customers who already knew how to navigate to the order form to select the TLC-10 3cc Syringe (part number 22722) they’re looking for.

I didn’t know a thing about their market sector. I researched it and interviewed the company’s principals and found out what they wanted.

It takes me two interviews, usually. My first interview shows me the vast cavern of emptiness of my knowledge of their sector. In the second interview, I’m educated-up to a level where I can ask intelligent questions.

I learned that you can buy PFPE from the competition for $400 a pint. How does TorrLube command a premium price of $5,000?

You couldn’t find out on their site. All they tell you is: they’re committed to working with engineers; they eliminate guesswork, they push the boundaries of what is known. Your headaches will decrease.

It was fun to learn about ultra-high-vacuum lubrication. Like a lot of tech companies, TorrLube was blasé about their own accomplishments because they were so familiar with their own esoterics. Their target audience was tribology engineers. There was no need to explain anything to their fellow engineers.

I looked at emails to TorrLube from engineers in the semiconductor

industry. Many of them said, “I know why your product is worth the

money, but I can’t get the suits and bean-counters to sign on.”

Part of the invisibility of TorrLube’s site is that they bill themselves as “unparalleled.” This may be true. But it doesn’t tell anybody anything. We don’t know what parallels are being talked about. The text gives us no foundation of knowledge to stand on.

So I created a clear plain explanation for them. I studied their information and interviewed the owner and the upper echelon of TorrLube staff to get more information. I studied their foremost competitors. I saw that every other manufacturer was selling their product as a commodity. You want PFPE? Click here to buy.

Then, I presented a draft of information and re-interviewed the TorrLube engineers, now that I had a glimmer of what they were doing. They corrected my mistakes and pointed out new things they hadn’t thought of mentioning before.

I pushed for more explanations of their technology. I told them that my plan was to write about their technology until I got it right, with them correcting me along the way.

And then I condensed TorrLube’s story into a 260-word elevator pitch: